SHEILA RAWLINGS

Following in my father’s footsteps

Articles

Last year, during the centenary of World War 1, I toured the war cemeteries and battlegrounds of Belgium. It was something I felt everyone should do, to remember the many thousands of lives that particular war had claimed. However, on my return it suddenly occurred to me that there was another conflict I should be giving more thought to. One in which my own father had fought – World War 2.

As a child, I was vaguely aware of my father's military involvement in the war, and that he had been captured by the Germans and held as a Prisoner of War (POW). However, it never really meant anything to me at the time, particularly as he was always reluctant to speak about it – apart from the odd derogatory comment hurled at the TV when watching a war film. It was only much later that the consequences of his experience began to register. Little things then started to make sense, like why he had a quick temper – something he apparently never had before the war – and why his cup always rattled in its saucer when he carried his tea to the table.

Like many relatives of POWs, I wished I had asked more questions when my father was still alive to answer them. Instead, as a result of my failure to show more interest, I was now faced with the task of researching his experiences myself.

With the much-appreciated help of organisations such as the Kew National Archives, the International Red Cross and the British Army Personnel Centre, it took me almost a year to gather all the necessary information I needed. Nevertheless, it was worth the effort because I now have a fairly comprehensive record of my father's wartime history.

However, although I had managed to piece together a fair account of my father's wartime experiences, there was still one thing left in order to complete the picture. I needed to travel to the site of his last POW camp and discover what life was like living as a 'guest of the Nazis'.

During my research I came across a Facebook group, created solely for the purpose of bringing together the relatives of POWs interred in Stalag 8b/344 Lamsdorf (now renamed Lambinowice) – the camp where, after being shunted around several other camps, my father had spent the last year of his four-and-a half years of captivity. Together with an extensive and dedicated website, it allowed people to share information, as well as providing useful tips to aid their research. What interested me most though was the opportunity of joining an organised visit to the site of the camp. Being the last piece in my research puzzle, I jumped at the chance to go. Therefore, at the beginning of September, I boarded a plane to Krakow and set off to join a group of like-minded people, all bent on seeing the place where their relatives had been incarcerated.

Known as Hitler’s slaves, the POWs were forced to work in labour camps – building roads or working on farms and in factories, etc. In my father’s case, he was forced to work down a coal mine.

DAY ONE: KRAKOW TO BLECHHAMMER

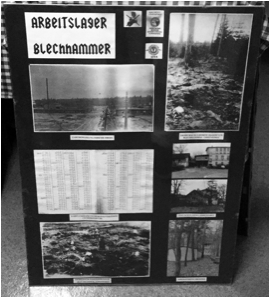

We began the first day by visiting Rakowicki Cemetery in Krakow, where 500 POWs from the Lamsdorf camp were reburied. From there we travelled to Blechhammer, where after lunch we visited the site of one of the work camps in which the POWs were forced to work – this one having been a German chemical factory. It now houses a small museum containing memorabilia and photographs of the period, including those of its reluctant workforce.

Considered a legitimate target by the Allies, the factory was bombed several times during the war, killing some of the POWs in the process. Although their presence in the factory was actually against the Geneva Convention – which stated that POWs should be kept away from the fighting – it was nevertheless not a detail to unduly worry the Nazis.

A personal journey of remembrance to Stalag 8b/344 Lamsdorf, Poland

Above: My father, George William Davis, photographed in 1947 – two years after his liberation by the Americans.

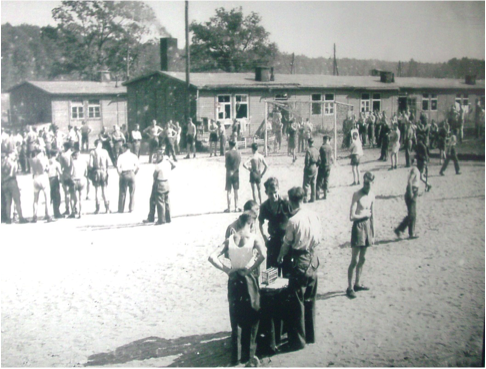

Right: Stalag 8b/344 Lamsdorf during World War 2.

As the camp at Lambinowice is just over 134 miles (216 kilometres) from Krakow, the journey was split over two days, with a stopover at Opole. In order to get to know each other before the trip, it was decided to meet up for dinner in Krakow the night before. Therefore, when our group boarded the coach the next day, we were all relaxed in each other's company and even managed to break the emotion of the occasion with a few laughs along the way.

Some of the photographs on display in the small museum at Blechhammer (‘Arbeitslager’ being German for ‘Labour Camp’).

Before we re-joined the coach, a local Polish TV station arrived to cover our visit for that evening's news bulletin. A clip of the news item was then posted on the Lamsdorf Facebook page and on viewing it I was surprised to see myself in the background. Albeit a case of 'blink and you will miss me', it was nevertheless my meagre claim to fame.

After 73 years, there is little left of Stalag 344 Lamsdorf and even less of its annex, Stalag 8b Teschen – to which my father was eventually transferred. This is now a housing estate. All that remains of the main camp are the buildings used by the German Commandant and his men, which now house the Central Museum of Prisoners of War in Lambinowice-Opole – the wooden huts in which the prisoners were kept having long since been replaced by woodland. However, the original road leading into the camp still exists, although it is now a simple woodland walk. Consisting of diagonal, cobbled slabs, it is lined by trees and referred to as Chestnut Avenue.

Finally arriving at the museum, we were welcomed with coffee and cakes before listening to two presentations: one given by the curator, Anna Wickiewicz, about life in the camp, and the other by her colleague, Sebastian, about the camp's evacuation and the Long March. Both were extremely informative and interesting and were followed by the opportunity to view a collection of documents, which Anna had managed to compile. These contained further details of some of the POWs.

After the presentations, we were then divided into two groups and given a guided tour of the museum. As we walked through the various rooms, it was obvious the staff had worked hard to collect and display a vast amount of memorabilia, documents, films and information to keep the memory of the camp alive. There was even a model of the camp in its original form, together with another detailed model featuring a section of a wooden POW hut.

Although there is no cafeteria at the museum, Anna had organised caterers to provide us with a typical Silesian lunch, which was held in the old German canteen. After the walk from the station, it was very much appreciated.

Because the camp was continually growing in size, Stalag 8b at Lamsdorf was eventually split into three parts and renamed. Apart from the main camp (which was renamed Stalag 344 Lamsdorf) and the satellite camp at Teschen (which was named Stalag 8b Teschen), there was also a separate camp for Russian POWs (Stalag 318/ 8f (344) Lamsdorf). This camp was very different from the other two.

Having an intense hatred of the Slavic nations, the Nazis used Stalin's refusal to sign the Geneva Convention as a good excuse for the appalling treatment of the Russian prisoners, who suffered far harsher conditions than most other POWs. The Russian camp was therefore probably more akin to a concentration camp. By comparison, the British POWs were relatively well treated – although 'relatively' is the key word, as it was certainly no walk in the park for them.

Built from concrete, the remains of the Russian buildings are still evident today – although, apart from one complete building, all that can be seen now are mostly the foundations. We spent some time wandering amongst the ruins before the coach took us to our final destination – a large, impressive memorial built on the site of a mass grave, where the bodies of thousands of Russian POWs are buried. As the Russian government displayed no interest in recovering them after the war, the memorial was erected as a tribute to the dead.

It was a long trip back to Krakow and therefore quite late when we arrived. Although it had been an emotional and exhausting two days, it was also a rewarding experience. As a result, when we flew back to the UK, we all had a far better knowledge and understanding of what our relatives had endured.

DAY TWO: OPOLE TO LAMSDORF (LAMBINOWICE)

After an overnight stay in Opole, we began the second day by travelling to a small railway station called Sowin. It was here that the POWs arrived in cattle trucks before being forced to march the remaining distance to the camp. Today, the railway station is disused, but a project is underway to renovate it. In order to get a feel for their journey, we decided to leave the coach and walk the remaining couple of miles ourselves. Fortunately, we were lucky with the weather and it was a pleasant walk. However, it was probably a different story for the POWs.

On the way to the camp we passed the old cemetery. As the camp had also been used for POWs during World War 1 – as well as originally for those in the Franco-Prussian war – the cemetery contained a variety of graves, all former prisoners of the Lamsdorf camp.

Sowin station, where the POWs arrived in cattle trucks before being marched to the camp.

Our guide, Anna Wickiewicz, (second from the left) described the conditions in which the POWs travelled to the camp.

TVP3 Opole, the local Polish TV station, arrived to cover our visit.

To get into the spirit, we decided to walk to the camp, just as our relatives had been forced to do – although fortunately we did it voluntarily.

The Central Museum of Prisoners of War in Lambinowice-Opole, housed in the former German Wehrmacht headquarters and guardhouse buildings.

Anna’s colleague, Sebastian, giving his presentation about the camp’s final evacuation and The Long March.

The remains of the original road to the camp.

A model of one of the wooden POW huts, showing a row of bunks either side of a solitary stove in each section.

Memorial commemorating the thousands of Russians who lost their life in the camp. It stands on the site of their mass grave.

For further information about POWs held at Stalag 8b/344 Lamsdorf, visit the following websites :

• THE CENTRAL MUSEUM OF PRISONERS OF WAR IN LAMBINOWICE-OPOLE

http://www.cmjw.pl/en/muzeum2/

• THE OFFICIAL STALAG VIII/344 LAMSDORF WEBSITE

https://www.lamsdorf.com/welcome.html

• CAPTIVITY IN BRITISH UNIFORMS: Stalag 8b (344) Lamsdorf

by Anna Wickiewicz

http://sklep.cmjw.pl/?95,ksiazka_93

PAST ARTICLES